An ongoing chronological compilation of references to and comments on the colonial Brisbane town boundary including:

• Boundary Street - Spring Hill,

• Boundary Street - West End,

• Vulture Street - West End and Woolloongabba,

• Wellington Road - East Brisbane

• the southern river bank from Wellington Road to Kangaroo Point,

- the existence and policing of a curfew for the exclusion of Aboriginals from the town at night during the 19th century,

- the relationship between the town boundaries and the curfew.

1) Did the curfew exist?

There is an large amount of published information that makes it clear that a curfew excluding Aboriginal people did operate, and was policed, in Brisbane and in many towns throughout Australia and that, at different times, the surveyed town boundary was used in some localities as a curfew boundary. As the town boundaries expanded to accommodate the growth of the town it meant that the legislated power of the Town Police increased to those wider areas such as Breakfast Creek and Herston Road. Certainly the Town Police were lobbied by colonial residents to increase the curfew policing to wider and wider areas.

There were occasions when the Town Police were censured for stepping outside their legal powers. There were occasions when fierce and emotive debate was presented in the papers of the time and when individuals spoke out against brutality and violence. This included criticism of oppressive and violent events in Brisbane by Sydney residents.

What is clear as well is that the published information comes from witnesses at the time, some of whom were opposed to the harsh, oppressive treatment being meted out and some of whom were calling out for even more control and more use of force.

3) Were Boundary Street, Spring Hill and Boundary Street, West End called 'Boundary' because of the curfew?

It would seem unlikely that Boundary Street in both Spring Hill and West End were given that name for any other reason than that they represented the location of the town boundaries in those locations. They and other streets such as Vulture Street and Wellington Road were used as curfew boundaries partly because the Town Police legal authority only extended to the legislated town boundaries. The section of town boundary along Boundary Street, Spring Hill only remained a town boundary for approx. 10 years.

4) Was the curfew legal?

I believe that there is sufficient evidence to conclude that the legislative basis of the curfew was the Police Towns Act or to give it it's parliamentary title 'An Act for regulating the Police in the Towns of Parramatta, Windsor, Maitland, Bathurst, and other Towns respectively, and for removing and preventing Nuisances and Obstructions, and for the better alignment of Streets therein.'

Under the Police Towns Act the Governor could appoint for each of the Towns listed under the Act a Justice of the Peace who would be or would appoint a Police Magistrate. This Magistrate was required to swear an oath to uphold the Police Towns Act including preventing and removing nuisances within the town. The duty of the Justice was to 'suppress all tumults, riots, affrays or breaches of the peace, all public nuisance and offences against the law and to uphold all regulations established by competent authority for the management and discipline of convicts within each of the said towns respectively.'

Under this act the Police Magistrate controlled the police, was able to hire and fire them and require them to obey the lawful commands of the Justice of the Peace.

As each town was added to the Police Towns Act the boundaries of the Town were described and gazetted and became the limit of the power of the Justice of the Peace, the Police Magistrate and the Town Police under his control.

As the towns enlarged so did the legislated boundaries and the ability of the Town Police to exclude people past the new boundaries.

I believe that, when colonial residents of the Moreton Bay colony and the township of Brisbane were lobbying for the police and government to 'maintain the regulation', it was these regulations sanctioned under the Police Towns Act that they wanted maintained.

Go To Summary Gazettal of Police Towns Act

5) How long did the curfew last?

There is no single answer to this question and probably no clear answer either. It is hard to be clear about when the curfew started. For example, was the different sort of exclusion that occurred during the Penal Settlement the start of the curfew?

The curfew excluding Aboriginal people from the town boundaries of Brisbane continued after Separation of Queensland from New South Wales.

There are first hand accounts of the curfew being policed in the 1870's. There are accounts of curfew policing in the 1880's when for example the South Brisbane Council restricted activities in Musgrave Park.

The passing of the Queensland state legislation called the 'Aboriginal and Islanders Protection and the Restriction on the Sale of Opium Act' of 1897 changed things in that all Aboriginal people were required to be removed to the reserves such as Deebing, Purga, Cherbourgh etc. There is a sense in which the Brisbane Town curfew is no longer required but the policing of curfews and even tighter controls in the reserves continued up until the 1970s.

6) What are the ongoing effects of the curfew?

I think it is fair enough to say that the institutionalized violence and oppression that was part of the Brisbane colonial curfew is still partly operating in more aggressive policing, racial profiling and the incarceration rates of Aboriginal people.

This page has been compiled and published in a spirit of reconciliation and truth telling and in the hope that it will provide useful and accurate information for people working towards that aim. It will be progressively updated as more information comes to my attention. I welcome suggestions of potential additions to the list of references. I would appreciate it if your use of this is acknowledged by publishing the URL for this page to help make its availability known.

It is my intention to compile a similar list of references to actions and statements of support for local Indigenous communities and individuals and would welcome contributions to such a list as well.

I acknowledge the Traditional Owners of the lands on which the town and its boundaries were created and the enormous impact of colonisation and the curfew on the vibrant Indigenous communities of this country.

Daryll Bellingham

1824 'The Moreton Bay Penal Colony'

The penal colony or settlement existed from 1824 to 10th February 1842 when Governor George Gipps declared it closed. The initiation of the penal settlement was effectively an invasion of the area and resistance was expected. Oxley's orders when sent to find a site for the penal settlement included the statement that the location should be 'easy of access, difficult to escape from, and hard to attack'.

Resistance continued during the penal settlement's occupation of both Kau-in Kau-in (Redcliffe) and Meanjin (Brisbane). The colonial authorities responded by moving camp to Meanjin but also by setting up guards to protect crops and remove the locals by force of arms, that is shooting them.

1829 'The 1829 Penal Colony Regulations'

• regulation 35 gives the Commandant the 'full authority to remove at his discretion, any Free person from the Settlement, who's Conduct shall appear to him to render this proceeding necessary for the due maintenance of discipline.'

• from 'Brisbane Town in Convict Days 1824 - 1842': J.G. Steele. p. 120

In other words, the Commandant would have been able to institute a curfew under this power and it is possible that this regulation may have helped set up a culture or expectation that people could be excluded from the settlement.

This does not indicate that a curfew was set up at this time however. There were calls after the shut down of the penal colony and the creation of the town for the Town Police to 'implement the regulation'. The question is which Regulation? In Sydney, Parramatta, Liverpool and Windsor the New South Wales colonial government were realising that they had to pass legislation to control a whole range of activities that were part of permanent housing, property buying and selling, commerce and 'man's best friend'.

1832 'An Act for the nuisance occasioned by the great number of Dogs which are loose in the Streets of the Towns of Sydney, Parramatta, Liverpool, and Windsor in the Colony of New South Wales'

This act was extended and morphed into the Police Towns Act which by 1838 included a range of other nuisances.

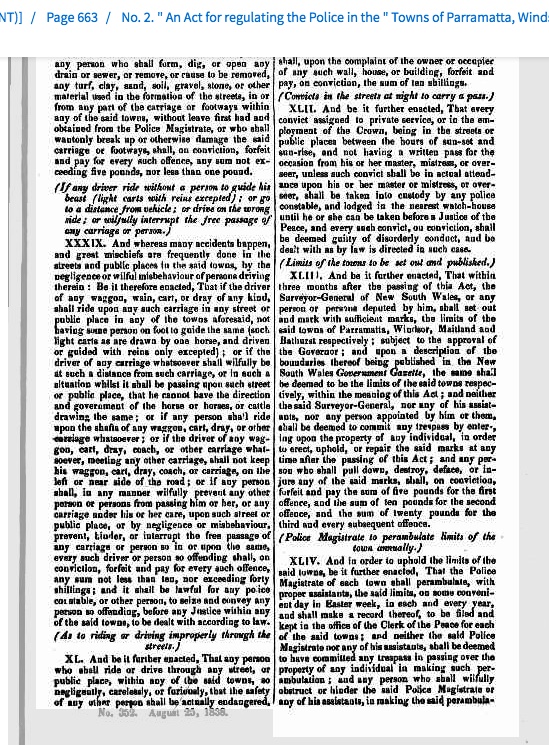

The 1838 Police Towns Act gave Town Police the power to apprehend drunk and disorderly people and take them to a Justice of the Peace or the nearest Watch House until they could be brought before a justice of the peace. It refers to any hour of the day but also between sunset and eight in the forenoon.

The 1838 Act is also very specific about a direction to mark the boundary of the town with sufficient marks and that the marks be maintained and repaired. Also any 'person who shall pull down, destroy, deface, or injure any of the daid marks, shall, on conviction, forfeit and pay the sum of five pounds etc...'

1833 Summary of the scope of the proposed Police Towns Act 12 June 1833

Colonial Secretary's Office, Sydney, I2th June, 1833.

HIS Excellency the Governor has been pleased to direct the publication of the general objects of the following Bill, now under the consideration of the Legislative Council. By His Excellency's Command, ALEXANDER M'LEAY.

" A Bill for regulating the Police in the town and port of Sydney, and for removing and " preventing Nuisances and Obstructions there in."

The Governor to appoint two or more persons as Police Magistrates for town of Sydney.

Police Magistrates to suppress riots, tumults, vagrancies, and public nuisances.

Police Magistrates, under authority of the Governor, to appoint a police force for the town and port.

Police Magistrates to make regulations for the management of police force, subject to the approbation of the Governor, and to have power to suspend and dismiss policemen.

Police to apprehend persons found drunk in the streets during the day, and idle, drunken, and disorderly persons lying or loitering between sunset and eight in the morning, in any yard, highway, &c, unless they give a satisfactory account of themselves.

Constables attending at watch-houses at night may take bail by recognizance from persons brought there for such lying or loitering, or for petty misdemeanor, for their appearance before a Magistrate.

Persons assaulting or resisting policemen, or aiding or inciting thereto, to be subjected to a penalty.

Publicans or other persons harbouring police-men, during hours of duty, to be subject to a penalty.

Police Magistrates to cause Lord's Day to be observed.

Games not to be played on Sunday under a penalty.

Persons assembling for that purpose to be dispersed, implements and animals seized, and those actually playing to be prosecuted.

Persons damaging any public work to be subject to a penalty over and above the amount of injury done.

Persons obstructing or diverting any water-course, or casting filth into the same, to be lined in addition to the expense of removal, &c.

Persons to be fined for wilfully injuring any public fountain, pump, &c, or clandestinely appropriating water thencefrom, or having a key for that purpose, or letting the water run to waste, or washing clothes thereat.

Persons to be fined for beating carpets, flying kites, breaking horses, driving barrows and carriages on footways, or throwing filth or rubbish in the street.

Persons to be fined for riding or driving furiously or negligently through the streets.

Persons to be fined for placing carriages, stall-boards, or goods, or timber, bricks, &c, and not removing same when required, or replacing same after removal, and the articles to be seized, and if perishable to be given to Benevolent Asylum.

This summary of what was being debated in the NSW parliament puts an emphasis (underlining is mine) on the role of magistrates to 'suppress' riots, tumults, vagrancies and public nuisances. However it includes a wide range of public offences that the majority of which were not specifically targeted at Aboriginal people. I think that it is quite reasonable to say that Police Towns Act was not specifically created to control Aboriginal people or to set up a curfew but that it certainly empowered Town Police to do so within the legislated town boundaries.

1838 Gazettal of the New South Wales 'Police Towns Act published on 11 September 1838

http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article36861999

Passed and Gazetted as 'An Act for regulating the Police in the Towns of Parramatta, Windsor, Maitland, Bathurst, and other Towns respectively, and for removing and preventing Nuisances and Obstructions, and for the better alignment of Streets therein .'

Section III included:- 'And be it further enacted, that it shall be the duty of the said Justices and restrospectively, to suppress all tumults, riots, affrays or breaches of the peace, all public nuisances, vagrancies, and offences against the law and to uphold all regulations established by competent authority for the management and discipline of convicts with each of the said towns respectively.'

When the Police Towns Act is gazetted in September 1838, the Governor could appoint for each of the Towns a Justice of the Peace who would be or would appoint a Police Magistrate. This Magistrate was required to swear an oath to uphold the Police Towns Act including preventing and removing nuisances within the town. The duty of the Justice was to 'suppress all tumults, riots, affrays or breaches of the peace, all public nuisance and offences against the law and to uphold all regulations established by competent authority for the management an discipline of convicts within each of the said towns respectively.'

As each town was added to the Police Towns Act the boundaries of the Town were described and gazetted and became the limit of the power of the Justice of the Peace, the Police Magistrate, and the Town Police under his control. He was able to hire and fire them and require them to obey the lawful commands of the Justice of the Peace. As the towns enlarged so did the legislated boundaries and the ability of the Town Police to exclude people past the new boundaries.

It is likely that based on the experience of the colonial government in Sydney, Paramatta, Windsor, etc in using this act to 'suppress all tumults, riots, affrays or breaches of the peace' or 'nuisances' that when Henry Wade was hired to survey the boundaries of the town of Brisbane at Meanjin so that it could be described under this Act, it is likely that he took into account the then localities of Aboriginal camps partly to make upholding of the Act easier for the Town Police and to establish a Town that could continue to develop in relative safety.

I believe that, when colonial residents of the Moreton Bay colony and the township of Brisbane were lobbying for the police and government to 'maintain the regulation', it was these regulations sanctioned under the Police Towns Act that they wanted maintained. Although neither a curfew nor Aboriginal people are specifically named in the Act there is obviously the ability to declare individuals and groups 'nuisances' or as causing 'tumults, riots, affrays' or, easiest of all as having committed 'breaches of the peace'.

(Back to Top)

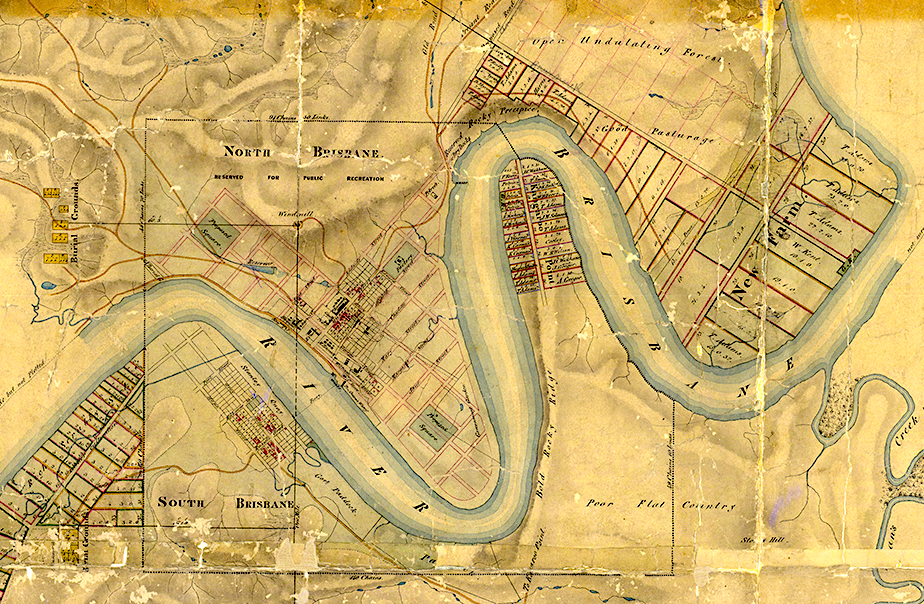

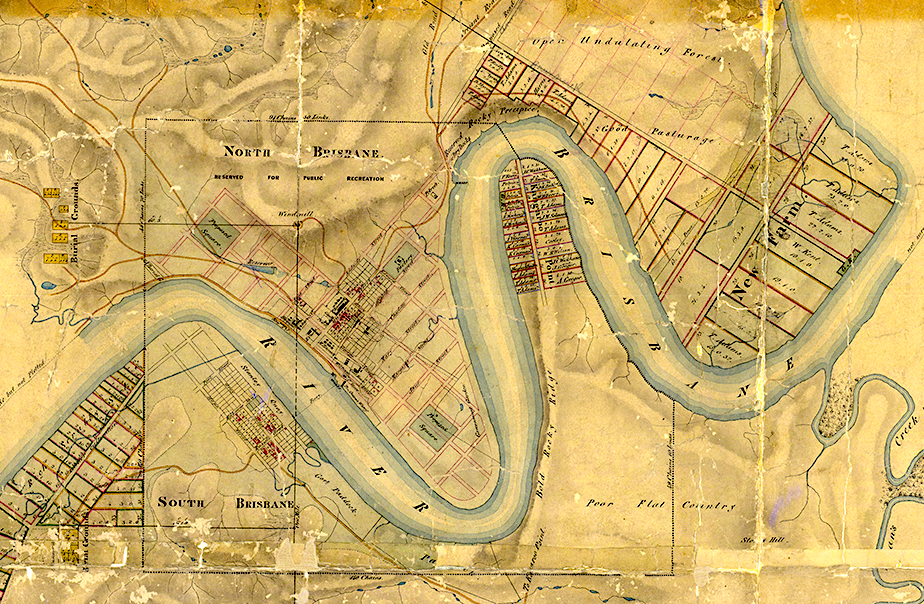

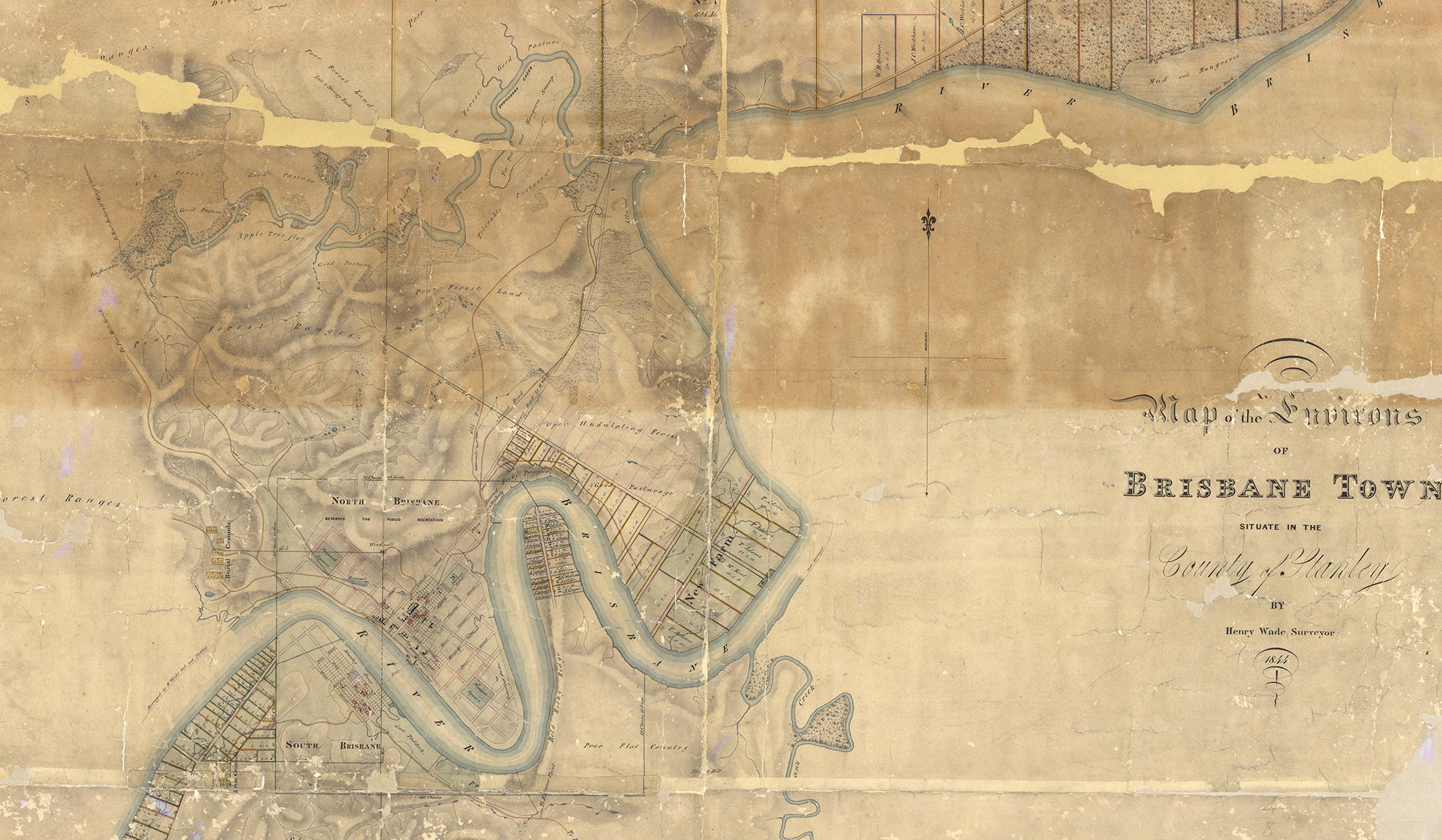

1842 Wade's survey of Brisbane, 1842

• MT5 Sunmap

• p. 78 of Brisbane the First 30 Years, W. Ross Johnston

This map shows survey of streets and allotments for sale on north side and on south side around Stanley Quay etc. and the town boundaries as below

It is possible that when Henry Wade surveyed the boundaries for the town of Brisbane at Meanjin in preparation for it being described under the Police Towns Act, he took into account the then localities of Aboriginal camps. Ray Kerkhove's work justaposing the location of Aboriginal camps with these surveyed boundaries shows how close these boundaries were to the existing camps. For example, the south east boundary, which in later years became Wellington Road, intersects with the river adjacent to a camp at what was to become Mowbray Park. Another camp was situated on a ridge immediately to the south of the Town Boundary that was to become Vulture Street.

1844 Henry Wade's plan of the environs of Brisbane, 1844, (above)

• MT12, Sunmap

• Qld State Archive, Public Domain - https://www.flickr.com/photos/queenslandstatearchives/41791195410/in/photolist-HgvV1D-26EWNpU

• p. 96, Brisbane the First Thirty Years, W. Ross Johnston

Shows the original surveyed town boundaries as described above and some surveyed allotments around Montague Rd. and around Stanley St., Grey St. etc. These planned boundaries are not yet streets ie Boundary St Spring Hill, Boundary St West End, Vulture St and Wellington Rd do not yet exist.

1844 Burnett's plan of the town limits

• MT11, Sunmap

• notes on map reads - 'This cancels former Survey by Mr. Wade ......... 18th Dec,1843. Boundaries proclaimed in the Gov. Gaz. for 1846 folio 537.'

• p. 82 Brisbane the First 30 Years, W. Ross Johnston

Plan shows boundaries as described above in Wade's 1842 survey but without the allotments that Wade put in his

1845 Kangaroo Point Pullen Pullens

SMH, p.2, 22 March 1845

'In my communication per Sovereign, I mentioned the assemblage of numerous tribes of blacks from the sea coast and adjacent country, who had congregated in the vicinity of this township for the purpose of having a pitched battle with the Brisbane and Logan blacks ; as was anticipated they did not separate without committing several depredations on the property of the residents in the vicinity of the settlement.

At the German missionary station, about five miles from this, the minga minga (sea coast) blacks, composing a body of fifty or sixty fighting men, surrounded the homestead, and after threatening violence to the white people, deliberately pulled the growing corn, about 300 bushels, and took away a quantity of potatoes, pumpkins, and almost every eatable article about the station. They then ransacked the houses, carrying off blankets, tin pots, wearing apparel, &c, leaving the poor Germans in great alarm for their lives ; their (the missionaries) pacific disposition prevented them from offering any resistance to the poor blacks.

Several industrious small settlers at Breakfast Creek, within a mile or two of the township, have been plundered of most of their garden and field produce. One of the white people, it is said, shot at a black fellow whilst in the act of stealing his corn, who subsequently died. Report says the body was conveyed across the river ; and a most singular feature in their habits of disposing of their dead was exhibited.

The tribe to which the aboriginal belonged, after various ceremonies being gone through, such as yelling over the corpse, scarifying themselves, &c., the body was dissected and cut up in sundry small portions, and distributed amongst the tribe, who, after eating the flesh from the bones, carefully scraped them, and were ultimately conveyed to the Logan-the district to which the deceased belonged, to be placed amidst the branches of a tree. There is no doubt of the above fact, of the flesh being eaten, as it is considered a mark of respect to the deceased by his tribe, as blacks belonging to a different tribe will not join in their cannibalism.

As past experience has shewn that whenever an assembly of blacks takes place, either for a corroboree or pullen-pullen, depredations on the white man's property are sure to ensue, owing to their hunger, from fasting the most of the time the dance or fight lasts; it certainly would be advisable for the authorities to put a stop when practicable, to these meetings, and as we have a military guard down here, the sight of a few bayonets, and an explanation through an interpreter of the unlawfulness of their meetings, would cause them to have the fear of the white man's anger in their heads.

The Brisbane tribe, generally speaking, from their intercourse with the white population, are pretty honest, and many of them daily frequent the township to perform sundry jobs for the inhabitants-fetching wood, water, &c. ; but the strange tribes are a complete pest when they are known to be in the vicinity nothing is too hot or too heavy for them to carry away, if in the eating line.'

This recount in the Sydney Morning Herald points out the dramatic cultural clash between European colonial culture and local Aboriginal cultural. It also demonstrates that the siting of the Penal Settlement and the town of Brisbane at Meanjin meant that they were being established on popular ceremonial meeting grounds.

1846 Police Towns Act came to apply to Brisbane

• p. 83 Brisbane the First 30 Years, W. Ross Johnston

• Johnston states in para three

As early as September 1843 Wade had prepared a plan of the town for police purposes. Burnett followed this up with a further plan six months later; this involved 'tidying up' central Brisbane to give it a clear identity. But almost two years elapsed before the government decided to bring Brisbane within the provisions of the Police Towns Act of 1839. The town limits were drawn roughly into the shape of a square, straddling the river. (45) Today the limits fall with Boundary Street on the north and west, Vulture Street on the south, and Wellington Road on the east. This act was aimed at the removal and prevention of nuisances and obstacles, and 'for the better alignment of the streets'. Wickham had complained in April 1846 that dogs, apparently without owners, were 'constantly prowling about'; pigs and goats were also a nuisance rambling about 'in search of food, destroying gardens, crops'. So the Police Towns Act and the Dog Act came to apply to Brisbane.' (46)

(45) Plans B1110, h.i. COD84, f.111; NSW, GG, 1846, 537 - The Police Towns Act and the Dog Act were extended to Brisbane.

(46) Police Magistrate to Colonial Secretary, 25 April 1846, (2 letters), 4/2735.2,SANSW.

1846 Description of Boundaries of the Town of Brisbane

• p. 42 Brisbane 1859 - 1959

• NSW Gov. Gazette, 5 May, 1846

'Commencing on the Brisbane River at the mouth of a small gully opposite Kangaroo Point, and bounded on the north by a line bearing west 91 chains 50 links; on the west by a line being 40 chains west from the centre of the Windmill, bearing south 45 chains 70 links to the Brisbane River, prolonged across that river, and thence south 60 chains; on the south by a line bearing east 140 chains; on the east by a line bearing north 49 chains 10 links to the Brisbane River, by that rivers upwards to the termination of the road running through Kangaroo Point, and thence by a straight line across the Brisbane River to the point of commencement.'

1846 W. Ross Johnston states in 'Brisbane the First Thirty Years' p. 114

'The hostility of the European community was increasing as the blacks made their stand. ............... Europeans put much blame upon the corroborees, the fights, the 'pullen-pullen' between different groups. ............... In July 1846 'one of the most desperate fights' between two Aboriginal groups occurred at Kangaroo Point. This led all 'right-thinking persons' to urge that 'such exhibitions may in future be prevented from taking place in the township'. The blacks needed to be 'checked', to be put in their place. Europeans concluded that these 'pullen-pullen' always ended in violence and depredations, partly because the Aborigines were hungry after fasting. So the cry went out that such gatherings should be stopped by the military, with bayonets on the ready.' (44)

44. SMH, 13 March 1845, p.2, 22 March 1845, p. 2; MBC, 25 July 1846, p. 3; T. Dowse, 'Diaries', 26 February 1845.

1847 Right of Might editorial arguing for the establishment Mounted Police

excerpt from Moreton Bay Courier, 16 January, 1847 Vol.1, No.31, page 3 'THE BLACKS' states

'We would recommend that the Protectorate should be abolished, and that with the funds, or one-half of the funds, a body of mounted police should be organised, in order that there should not be a spot where the settlers reside where their presence is not known and felt: this force to be placed under the command of intelligent and humane officers, who will be the guardians of the black as well as of the white. Let minor offences be tried on the spot where they are committed. The natives would soon become aware that they would be severely punished for their outrages, and the result would be that they would gradually and quietly be reclaimed, and they would then assist the settlers in their toils, and receive adequate remuneration. We have seized their country by the right of might, and by the right of might the whites will continue to possess it. When all other remedies, and amicable means, have failed, they ought to be civilized by compulsion. If the writer will apply himself to the study of this question, and devise means for the amelioration of their present wretched condition; if he will treat the subject practically instead of theoretically, we will go hand in hand with him to effectuate his plans. We have been maliciously accused of advocating the utter destruction of' the aborigines. Those who are acquainted with our principles know this to be a gross calumny. What we have always advocated is the meting out equal justice to all, whatever their station in life, creed, or colour.—ED. M. B. C.].'

http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article3709699

Bolding in article above is mine (DKB)

Page 4 of MBC states - Printed and Published by the Proprietor, Arthur Sydney Lyon. He is likely to have been editor of this edition and the author of the article. This editorial was in answer to the criticism of a Sydney Chronicle letter to the editor about the shooting of Horse Jemmy by armed prisoners with a warrant issued for his capture on the promise of a conditional pardon.

1847 Perambulation of the Boundary of the Town

10th April, 1847, Moreton Bay Courier, Page 3

Boundary of the Town. - On Thursday the Police Magistrate and Lieut. Blamire, J.P., with their assistants, Mr. Wm. Fitzpatrick, Chief Constable, and James Ramsay and Henry Finlay, constables, perambulated the limits of the town, in accordance with the 44th section of the Towns' Police Act, which enacts that the Police Magistrate shall, in order to uphold the limits of each town, proceed on some convenient day in Easter week, in each year, to perambulate the boundary, and make a record thereof, to be filed and kept in the office of the Clerk of the Peace. This is the first time the ceremony has been performed, the provisions of the Police Act not being in force at the same period last year.

1852 Petrie's engaged to mark out the Boundary of the Town

https://www.petrie.com.au/timeline

"The Petrie’s were engaged to mark out the boundary of Brisbane. They undertook this and placed posts at convenient intervals along the town boundary to divide it from the suburbs. As well as placing posts along leading streets to mark the footpath and the street. The work was done by John Petrie for £84. The marking out of the main streets and the boundaries of the town was seen to be improving the appearance of the town."

(excerpt from the Petrie's web site timeline)

(Thanks to Melissa Goorie for suggesting this post and the date.)

1853 'Wars of Kangaroo Point' - a comment on the legality of discriminating against Aboriginal men within the town

DOMESTIC INTELLIGENCE. (1853, October 8). The Moreton Bay Courier (Brisbane, Qld. : 1846 - 1861), p. 3. Retrieved July 27, 2021, from http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article3709900

THE WARS OF KANGAROO POINT.

- On Sunday last the pleasant locality of Kangaroo Point was the scene of a disturbance which occupied the Police Bench for a considerable time yesterday forenoon, and, better still, gave employment to all the officers of the Customs department. Mr. Duncan, Comptroller of Customs, presided on the Bench; Mr. Sheridan, Tide Surveyor of Customs, was a witness in one case and defendant in another; and Mr. Garling, Clerk of Customs, gave evidence in both cases.

The cases arose out of an alleged unwarrantable interference on the part of Constable William Gilpin Watts, with the Sunday afternoon amusement of some native blacks, at Kangaroo Point. At about six o'clock on Sunday afternoon. Constable Watts saw four blacks, who are employed as servants by some gentlemen at Kangaroo Point, amusing them-selves opposite Mr. Sheridan's door by throwing small sticks at each other, in imitation of a spear fight. The sticks were but slender, and blunt, but some of them were thrown across the street, and might have struck the children who were about; and the constable, having orders to keep the blacks out of town on Sundays, immediately ordered them to desist, and go away. One of the blacks was lying on the ground when the constable came up, and the latter just touched his foot with his stick, and ordered him to rise.

Here Mr. Sheridan interfered, and thus arose the first case tried yesterday, for he was summoned for this interference. Constable Watts swore distinctly that Mr. Sheridan said that if he was in the place of the black he would kick--&c., making use of a gross expression towards the constable, and that he also accused the constable of being like those on the north side of the river, who had frequently injured the blacks, or some-thing to that effect. Mr. Alexander Brown corroborated the evidence [sic] of this witness in its main points, and swore positively to the indecent expression used. On the other hand Mr. Sheridan stated in defence that he only remonstrated with the constable for unnecessarily interfering, as the blacks were not on the street, but on a green in front of his (Mr. Sheridan's house), and that he never used the indecent part of the expression attributed to him.

Mr Garling gave evidence to this effect, and stated that the indecent word was not used, although Mr. Sheridan said he would kick the Constable if he was in the place of the blacks. In the course of the examination Constable Watts mentioned the fact that one of these blacks was reeling about Kangaroo Point at night, beastly drunk.

Mr. Sheridan remarked that the blacks alluded to were as respectable and moral as the Constable, and the latter then appealed to the Bench whether such a remark ought to be permitted, but Mr. Duncan said that the defendant had a right to express his opinion.

After consulting with Mr. Fairholme, who was also on the Bench in this case, the presiding magistrate said that the orders under which the Constables acted in keeping the blacks out of town on Sundays, were illegal, and therefore Mr. Sheridan might have considered himself justified in interfering.

As to striking the black on the foot, the constable had no right to do it, and it was an assault. But as he had instructions to keep the blacks away on Sunday he most likely thought he was doing his duty. There the case must rest.

- Next appeared Mr. Henry James Sloman, to answer a charge of using obscene language to Constable Watts on the same occasion. The evidence of the Constable went to show that Mr. Sloman had interfered when he ordered the blacks off, had given him much abuse, and used a filthy and obscene expression. This evidence was fully corroborated by Mr. Alexander Brown, and another witness named Broadfoot. Defendant denied the charge, and called witnesses to disprove it. William Macdonald and Mr. E. H. Alcock, swore that they were present and did not hear the expression alluded to used by defendant, and that they thought they must have heard it if it had been used. Macdonald, however, did not give his evidence in a very straightforward manner. Mr. Sheridan and Mr. Garling were also called, but the former was not present at the altercation, and the latter, evidently to the dis-appointment of the defendant, distinctly swore that he did use the obscene word imputed to him.

Mr. Sloman, in defence, was eloquent, but decidedly unconnected. He declared that he had never used such an expression in his life, and then diverged to a charming picture of the amiable and peaceful demeanour of the Kangaroo Point folk generally, whom he described as being "red hot from Church" on the occasion alluded to, and not at all likely to be guilty of the conduct imputed, to them by the constable.

He had only interfered, he said, to prevent the constable ill-using the blacks. Mr. Duncan, although determined on ordinary occasions to deal severely with cases like this, which he held to be proved, was yet of opinion that the constable had acted in a provoking manner, particularly by threatening to put handcuffs on Mr. Sloman, which he had no right to do. He would therefore only inflict a fine of 10s. with 23s 6d costs, which was paid.

What can we read from this article. The title is interesting. Is it referring to recorded 'pullen pullen' events at Kangaroo Point or is it referring to a 'war' between those who want to actively police a curfew against Aboriginal people and those who don't.

Mr. Sheridan likely employed Aboriginal servants and he very actively argued with Constable Watts about Watts attempting to remove them from the town.

There is a specific reference in the Police Towns Act to not playing sport on a Sunday.

Magistrates Fairholme and Duncan both considered that Constable Watts was acting under 'illegal' orders. This raises the question of 'whose orders?' - another Magistrate, the Chief Constable?

1855 Camp at One Mile Swamp - Curfew active

Ray Kerkhove quotes Perry - 'Memoirs of the Hon. Sir Robert Philp, K.C.M.G., 1851 - 1922' by Harry C. Perry, Brisbane: Watson, Ferguson & Co., 1923.)

'From 1840 to 1855 Aborigines moved quite freely around the settlements, but after 1855 Blacks were prohibited from venturing inside Vulture and Boundary Streets after 4 p.m. or on Sundays.'

Perry wrote p 21-

'Further on was the One Mile Swamp now the Brisbane Cricket Ground. This locality provided a favourite camping ground for the aboriginals, of whom there was a considerable number about. Because of their predatory instincts they were compelled to withdraw from the confines of the town by 4 o'clock each afternoon.'

One wonders if Sir Robert Philp may have been being a bit casual with his claim about freedom of movement from 1840 to 1855.

The One Mile Swamp camp would have been just outside the Town Boundary. Were the town boundaries partly drawn up with the camps in mind?

1856 Extension of the Police Towns Act to the Town of Brisbane

'Moreton Bay Courier (Brisbane, Qld. : 1846 - 1861), Saturday 16 August 1856, page 2

DOMESTIC INTELLIGENCE.

EXTENSION OF BRISBANE TOWN BOUNDARIES PROCLAMATION

( From Government Gazette, August 1.)

By his Excellency Sir William Thomas Denison, Knight, Governor-General in and over all her Majesty's colonies of New South Wales Tasmania, Victoria, South Australia, and Western Australia, and Captain-General and Governor-in-Chief of the territory of New South Wales and its dependencies, and Vice-Admiral of the same, &c., &c., &c. Whereas in pursuance of an Act of the Governor and Legislative Council of New South Wales, passed in the second year of the reign of her Majesty Queen Victoria, intitaled, "An Act for regulating the Police in the towns of Parramatta Windsor, Maitland, Bathurst, and other towns, respectively and for removing and preventing nuisances, and obstructions, and for the better alignment of streets therein," the provisions of the said Act were, by a proclamation of the thirtieth day of April, in the year of our Lord one thousand eight hundred and forty-six, extended to the Town of Brisbane, in the District of Moreton Bay; and whereas it was by the said Act amongst other things enacted, that, upon a description of the boundaries of such town being published in the New South Wales Government Gazette, the same should be deemed to be the limits of the said town;

Now, therefore, I, the Governor-General aforesaid, with the advice of the Executive Council, do hereby direct that the following shall be deemed to be the boundaries of the said town of Brisbane, for the purpose of the said Act, that is to say:-

Commencing on the left bank of the Brisbane River, at the southern extremity of the north-west side of the road dividing John M'Connell's 13 acres 1 rood and 2 perches, and 21 acres 3 roods and 4 perches, and bounded on part of the east by the north-west side of that road north-easterly to the south corner of J. C. Wickham's 30 acres; thence on the north by the south-west boundary of Wickham's 30 acres and the south-west side of the road which forms the south-west boundary of James Gibbon's 86 acres and 33 acres and T. Shannon's 13 acres and 19 perches, to the new bridge on the Eagle Farm Road; thence by lines north-westerly, in all 37 chains and 24 links, up the north side of York's Hollow Swamp, to a point west of the old road to Eagle Farm, and opposite to the ridge which divides York's and Spring Hollows; thence by lines south-westerly to and along that ridge and the ridge forming the southern watershed of York's Hollow, to a point north by compass from the north-east corner of the Jews' Burial Ground for North Brisbane; and on the west by a line bearing south and forming the eastern boundaries of the Jews' Roman Catholics,' Presbyterians,' and Aborigines' Burial Grounds, to the north corner of D. R. Semer… 3 acres and 8 perches, by the south-west side of the road forming the north-east boundary of that land, to a small creek which forms its south boundary, and by that creek to the Brisbane River by a line south-easterly across the Brisbane River, to the north extremity of the west side of Boundary street, South Brisbane, being the north corner of John Croft's 2 acres, and by the west side of Boundary-street southerly to the south side of Vulture-street ; on the south by the south side of Vulture-street and of the road in continuation thereof; easterly to a point due-south of the south-east corner of W. Kent's 6 acres 1 rood and 13 perches, and on the remainder of the east by a line north to that point, by the west side of the road founding Kent's land, on the east, northerly to the Brisbane River, by its extension northerly across that river, and by the left bank of the river upwards to the point of commencement.

Given under my hand and Seal, at Government House, Sydney, this twenty-eighth day of July, in the year of our Lord one-thousand eight hundred and fifty-six, and in the twentieth year of Her Majesty's Reign.

W. DENISON.

By his Excellency's Command;

STUART A. DONALDSON.

GOD SAVE THE QUEEN !

http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article3713175

What follows is a description of the new extended town boundaries. This proclamation by the Governor General establishes the new extended Brisbane Town boundaries in legislation and re-establishes a use for those boundaries, i.e., 'for regulating the Police in the towns' and 'for removing and preventing nuisances, and obstructions, and for the better alignment of streets'. The new boundaries are now extended north to Breakfast Creek and 'the new bridge on the Eagle Farm Road' and then north-westerly to the 'Yorks Hollow Swamp' then south westerly past the north side of the 'Jew's Burial, along a small creek to the Brisbane River and across to Boundary Street and Vulture Street.

This means that the old 1846 Boundary Street, Spring Hill section of the town boundary is no longer in use.

Did the change come about after 10 years of growth and subdivision of Brisbane town or is this also a reponse to a perceived need to extend the curfew boundary out to where the Breakfast Creek Aboriginal Camps were and enable the legal use of the Town Police for the purpose?

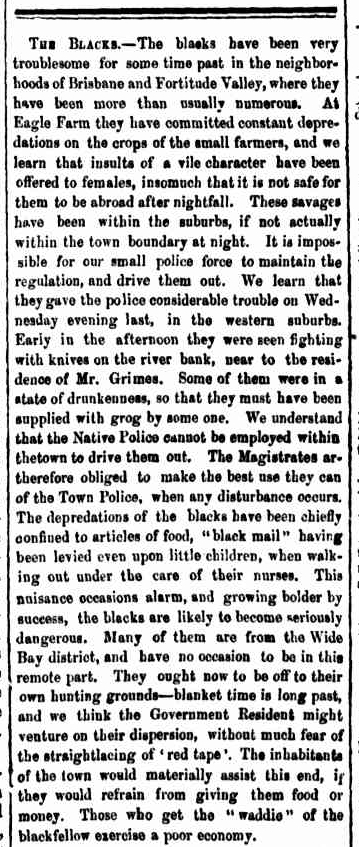

1858 Lobbying to drive out 'these savages' from the town and the restriction of the use of Native Police within the town

The Moreton Bay Courier (3/7/1858 p.3) is quoted by Rod Fisher in 'From depredation to degradation.

- Brisbane the Aboriginal Presence 1824-1860' p. 35 as saying -

'These savages have been within the suburbs, if not actually within the town boundary at night. It is impossible for our small police force to maintain the regulation, and drive them out. ..................... We understand that the Native Police cannot be employed within the town to drive them out. The Magistrates are therefore obliged to make the best use they can of the Town Police when any disturbance occurs. ................................' (12)

The words 'maintain the regulation' point to the possibility of an actual regulation here. It is likely that it is referring to the Police Towns Act and the requirement of the Justice of the Peace / Police Magistrate to suppress disturbances and nuisances. However a lot of the powers related to controlling nuisances were specifically talking about dogs, pigs, rubbish, sewage, shop displays that went too far out into the street, pollution etc. Nowhere are Aboriginal people mentioned in the Police Town Acts but there is obvious requirements to regulate and to 'frame orders', 'ensure there are sufficient of constables for preserving the peace' 'within the limits of the said towns'.

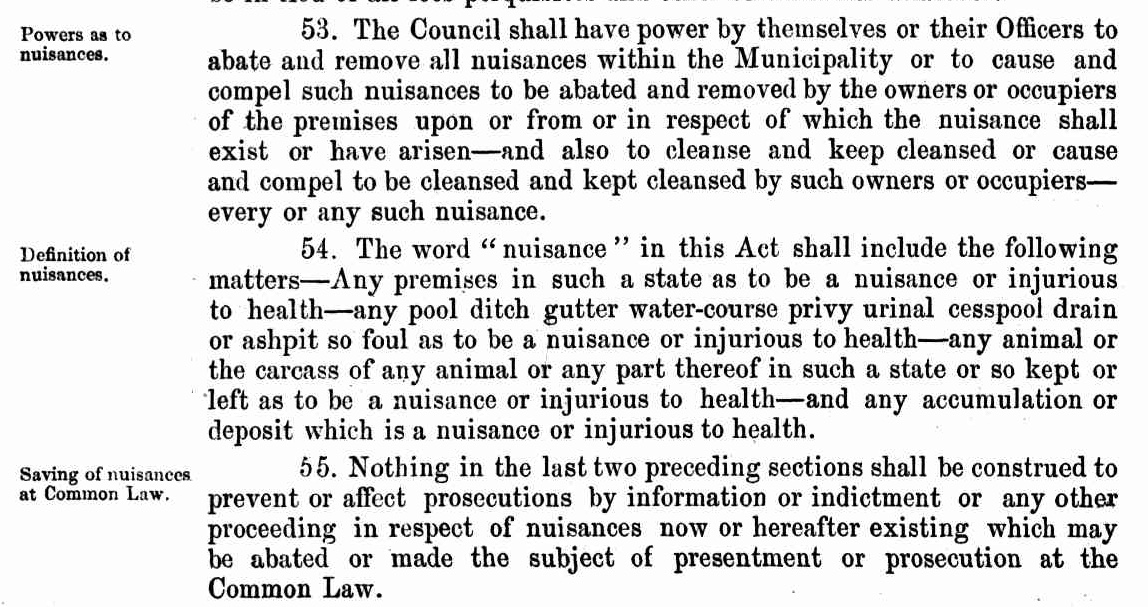

Extract defining nuisances from the 1588 Municipalities Act. Although the act states that the word 'nuisance' in the Act shall include the following matters.... It does not say that the definition is restricted to these things and goes to the trouble to make it clear that the defined meaning will not prevent or affect prosecutions related to nuisances in the Common Law.

The Town Police also had the power to apprehend drunk and disorderly, take them to a Justice or to the nearest Watch House.

The Chief Magistrate was also required to command the Town Police to act against nuisances however and could also censure them for acting outside the powers of the Police Towns Act.

1859 'The Municipalities Act of 1859'

from 'Memoirs of the Hon. Sir Robert Philp, K.C.M.G., 1851 - 1922' by Harry C. Perry, Brisbane: Watson,Ferguson & Co., 1923. p. 19

'After a preamble setting out that the Proclamation was issued under the provisions of the New South Wales Act entitled 'The Municipalities Act of 1859,' pursuant to a petition from the residents, the Proclamation goes on to declare the boundaries of the new Municipality in the following most interesting language.'

What follows is the description of the boundary as previously.

In the Municipalities Act the Councils were able to appoint Inspectors of Nuisances with powers to impose and collect fines for the usual run of nuisance and rather more specifically dead animals, sewage, factory smells etc.

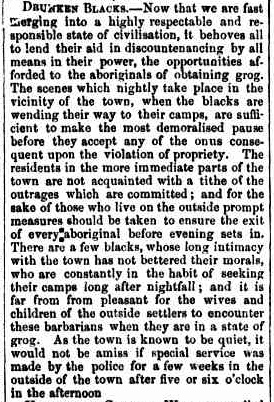

1859 'Lobbying for 'special service' by police outside of the town

from Moreton Bay Courier, 20/12/1859, P2, Local Intelligence

'DRUNKEN BLACKS. Now that we are fast merging into a highly respectable and responsible state of civilisation, it behoves all to lend their aid in discountenancing by all means in their power, the opportunities afforded to the aboriginals of obtaining grog. The scenes which nightly take place in the vicinity of the town, when the blacks are wending their way to their camps, are sufficient to make the most demoralised pause before they accept any of the onus consequent upon the violation of propriety. The residents in the more immediate parts of the town are not acquainted with a tithe of the outrages which are committed; and for the sake of those who live on the outside prompt measures should be taken to ensure the exit of every aboriginal before evening sets in. There are a few blacks, whose long intimacy with the town has not bettered their morals, who are constantly in the habit of seeking their camps long after nightfall; and it is far from from pleasant for the wives and children of the outside settlers to encounter these barbarians when they are in a state of grog. As the town is known to be quiet, it would not be amiss if special service was made by the police for a few weeks in the outside of the town after five or six o'clock in the afternoon.'

LOCAL INTELLIGENCE. (1859, December 20). The Moreton Bay Courier (Brisbane, Qld. : 1846 - 1861), p. 2. from http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article3718652

In other words some sort of curfew is in place and has worked for the town proper and the MBC was wanting an unofficial extension into the suburbs - 'prompt measures should be taken to ensure the exit of every aboriginal before evening sets in'. The term 'special service' is obviously an euphemism for some sort of police action outside the ordinary. We can only guess exactly what was meant.

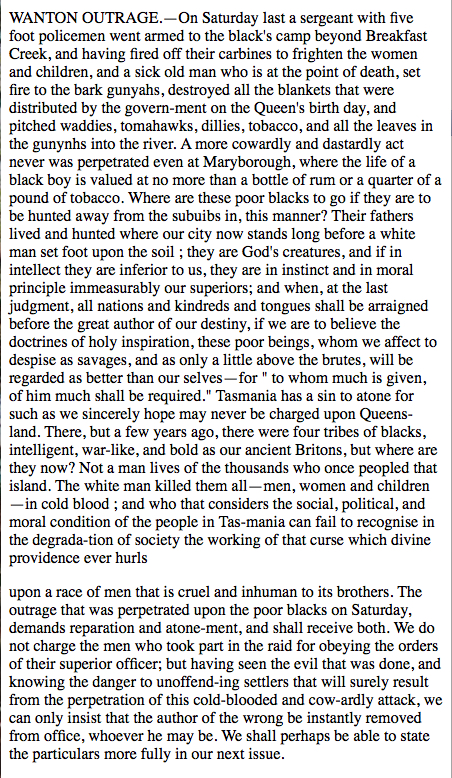

1860 - Wanton Outrage about the attack on the Breakfast Creek camps 6th October 1860

On Tuesday the 9th October the Moreton Bay Courier published an article condemning the attack on and the destruction of the camp on the other side of Breakfast Creek.

'WANTON OUTRAGE.- ON Saturday last a sergeant with five foot policemen went armed to the black's camp beyond Breakfast Creek, and having fired off their carbines to frighten the women and children, and a sick old man who is at the point of death, set fire to the bark gunyahs, destroyed all the blankets that were distributed by the government on the Queen's birthday, and pitched waddies, tomahawks, dillies, tobacco, and all the leaves in the gunyahs into the river. .............. Where are these poor blacks to go if they are to be hunted away from the suburbs in this manner? Their fathers lived and hunted where our city now stands long before a white man set foot up the soil; ............'

October 1860 - Inquiry into the Burning of the Breakfast Creek Camps

Moreton Bay Courier (Brisbane, Qld. : 1846 - 1861), Thursday 18 October 1860, page 2

THE LATE OUTRAGE ON THE BLACKS.

On Thursday last an important investigation into the late outrage upon the blacks near Breakfast Creek was commenced at the Central Police Court, and concluded Tuesday, before the Police Magistrate, the Mayor, and Mr. T. B. Stephens. The enquiry is an important one, if it were only to illustrate the circumstances under which the unfortunate blacks are permitted to exist in their native land, and to suggest some improvement in their future government.

Thomas Francis Quirk, chief constable in the Brisbane police, deposed as follows:—In consequence of information received, and the complaints of persons at Eagle Farm, to the effect that the blacks, were very riotous, exposed their persons, and otherwise behaved in an unbecoming manner, I directed Sergeant Apjohn and four constables on Saturday last to proceed to the blacks camp for the purpose of removing them. The sergeant and constables left at 3 o'clock, and returned at 6 o'clock. Sergeant Apjohn was in charge, and my instructions to him were to order the blacks to remove, and to take with them their blankets, tomahawks, &c. The sergeant on his return reported to me that the blacks had removed without any harsh measures having been adopted.

[Witness here read the report. ] It is in Apjohn's hand-writing.

The police went with guns and ball-cartridge; I did not tell them to take ball cartridge; I merely ordered them to take their arms and usual appointments. The carbines taken on the occasion were loaded because they were those used by the police guard in charge of the prisoners from the gaol, and they were discharged at the blacks' camp because it is customary to discharge them once a week beyond the precincts of the town. They were not fired at the blacks. The report just read was sent in yesterday ; there was another one sent in immediately after the occurrence took place. The report read to the court is contradictory of certain statements in the 'Courier' newspaper. I have had repeated complaints regarding the conduct of the blacks, and on one occasion it was reported to me that they were fighting opposite Cameron's, and behaving themselves in a most indecent manner. I am sixteen years in connection with the police; it is not usual in Sydney for the inspector or chief constable to report to the police magistrate or inspector-general of police before taking action. The inspector acts according to his own discretion, and is responsible only to the inspector-general of police or the police magistrate. After having acted he reports the matter to his superior officer, and if it turns out that he has exceeded his duty, he is liable to be called to account.

Mr. Brown (P.M.): I must inform you that in future you will not act without in the first instance reporting the matter to the bench.

William Apjohn, Police Sergeant, deposed as follows:—In consequence of orders received from Mr. Quirk, I with four constables proceeded at 3 o'clock on Saturday last to the blacks' camp beyond Breakfast Creek. We were ordered to chase the blacks from thence and to set fire to their camps. I proceeded thither with four constables, namely, Cox, Balfrey, Burke, and Dunning. The first camp we came to was about two yards from the road on the river side, and half a mile from the bridge. Mr. Quirk told us that the blacks had committed depredations and that we were authorised to remove them. We took with us ball cartridge

[Mr. Quirk here proceeded to interrupt the sergeant, upon which Mr. Brown said— "Sit down, Sir, we cannot allow the witness to be thus interrupted." Mr. Quirk then endeavored to explain his meaning to the bench, and having persisted in doing so, Mr. Brown at length said, "If you will not be silent, Mr. Quirk, I shall order you out of court." Mr. Quirk was understood to reply in a subdued tone that he was never before so much insulted by a gentleman on the bench.]

The witness proceeded. The carbines were not capped at the time we went to the camp. I told the blacks to remove, which they did not seem to understand; but another constable said they must "settle," which I believe they understood, as they soon after went away, some into the bush, and others into a boat on the river. After they went away we set fire to their gunyahs, and destroyed them; the carbines were not fired at this time. I do not know whether any of their blankets were burnt or not, but I gave orders that they should not be burnt, as they were given by the government. While the camp was on fire I saw a tomahawk, which I ordered a constable to throw to the black fellows, and it was done. At the same time I cautioned the men not to fire on the blacks. The burning of the camp occupied about twenty minutes; the camp was not set on fire until about ten minutes after the order "to remove" was given. The number of blacks present was about fifty, and the number of gunyahs burnt about twenty-five. I cannot say whether any of their blankets, bread, &c., were destroyed, or whether any of their tomahawks or other implements were thrown into the river. I believe they took their blankets with them. Before burning the camp a diligent search was made, and I saw no blankets, or bread, or anything else, with the exception of a fig of tobacco, which was handed to me by a constable.

I acted strictly in accordance with the instructions given to me by the Chief Constable. The blacks left quietly when the order to remove was given. We followed them up the hill, where there was another camp, and fired our carbines into a tree; I followed them because I knew there was a camp on the hill. I told the men to fire at the tree without any other purpose than that of discharging our carbines, which we generally did once a week. I gave the order to cap the carbines and one of them was discharged by a Mr. Black. We destroyed the camp on the top of the hill in the same way as we did the former, after the blacks had removed. I then returned to Brisbane, and reported the occurrence to Mr. Quirk, first verbally, and then in writing.

I sent another report in yesterday. It is not usual to send in two reports with reference to one matter. It was done at the request of Mr. Quirk, in consequence of a paragraph that appeared in a newspaper.

There were five carbines fired altogether, and of these I think two were reloaded and discharged. There were not more than seven shots fired, and four of these were fired at one time. I do not know how many rounds of ball cartridge we had with us. It is not usual to attempt to quell a riot without knowing whether the men have sufficient ammunition. There was not one of the shots fired in the direction of the blacks The shots were discharged before the gunyahs were set on fire, and I believe the first was fired by Constable Cox. This took place about two minutes after the gunyahs were set fire to. The shot was fired in an opposite direction to that in which the blacks were, as were also the other shots. I saw no bread, or anything belonging to the blacks, thrown into the river. There were four constables present when I received instructions from Mr. Quirk. The instructions were to go out to the camps, chase the blacks away, set fire to their camps, and "let your carbines be discharged." The object in discharging the carbines was merely to unload them, which was customary once a week.

William George Chancellor deposed as follows:—On Saturday last, I was out riding with some gentlemen in the vicinity of the blacks' camp at Breakfast Creek. I saw smoke at the first camp, and on proceeding thither I found the gunyahs had been burnt. I then went up to the top of Louden's Hill, in company with the police, and there also saw the blacks camp on fire, but I saw no blacks. I saw a few old blankets lying on the ground, and the policemen pulling down the gunyahs. I also heard shots fired before I went up the hill, but owing to the density of the scrub I could not see who were the parties firing. Everything belonging to the blacks, including spears, waddies, &c., was burnt by the police. I only saw two blankets in the burning gunyahs, but there might have been more. Owing to the scrub I could not see in what direction the shots were fired. I was not there at the commencement of the burning, but the gunyahs on the road-side were all destroyed. and afterwards I saw those on the hill burnt. There were two gentlemen with me at the time, one of whom was Mr. South.

Henry Cox, a constable in the Brisbane police, made the following statement:—I was ordered on special duty on Saturday last by Mr. Quirk. Sergeant Apjohn was in charge. I did not hear the instructions given, but in consequence, we took our firearms with us, and proceeded to the blacks' camp on the Eagle Farm road. We took our fire-arms and appointments with us, and went to the blacks camp, a little beyond Breakfast Creek, on the Eagle Farm Road. Among the blacks present there were women and children; shortly before reaching the camp we saw some blacks passing along the road, and Sergeant Apjohn told them we were sent to drive them away from the camp, and when we arrived at the camp the same information was repeated by Sergeant Upjohn. At his request the blacks immediately began to clear out, taking with them their blankets, nets, and other property. They had a sick man among them whom they removed into a boat; whilst they were removing the sick man, I saw constable Burke remove some nets, tomahawks, &c., so that they should not be burnt; I also saw the blacks taking away their blankets and other property; they had their arms full on leaving the camp, and I assisted to remove several of the things myself. Some of the blacks went into the bush, and others went into a boat with a sick man whom they carried. [This man died on the Monday.] It was nearly half an hour after our arrival before a fire stick was put to the first gunyah. The gunyahs were all burnt down before any shots were fired. Sergeant Apjohn fired the first shot; it was at a gum tree; I fired the third or fourth. There were altogether four shots fired at the camp near the river. Sergeant Apjohn gave the order to cap as it was usual to discharge our carbines on a Saturday. We then went to the camp on the top of the hill, but there were no blacks there; they had all left before we arrived. There might have been 50 or 60 blacks there before, as the camp was a very large one ; we commenced firing the camp immediately. I followed the example of Sergeant Apjohn who said he supposed the blacks had left in consequence of having hear them firing below; the shots were fired after the burning commenced ; there were about eight shots fired altogether. I did not see any blankets, bread, tomahawks, or tobacco belonging to the blacks burnt. I can swear that nothing belonging to the blacks was thrown into the river in my presence, neither did I see any of the blacks ill-used ; I saw three gentlemen on horseback near Breakfast Creek, but I do not know their names.

[The case was here adjourned until Monday.]

Frank Charles South having been sworn, deposed as follows :—On Saturday week last I was out with three gentlemen riding in the vicinity of Breakfast Creek. One of our party met with an accident, and while we were attending to him a body of foot police came up; there were two blackfellows present at the time, and one of the police told them that they (the police) were about to turn them out, or something to that effect. The police then left apparently for the purpose stated. In the meantime I went down to a house to see after the gentleman who had met with the accident, and shortly after I heard the report of fire arms. On looking in the direction of the camp I saw smoke, and immediately after mounted my horse and proceeded thither. The first camp I saw was that on the bank of the river a little beyond Breakfast Creek. I saw the policemen fire, but the blacks were all gone; the huts, however, were on fire. The police then went up the hill to another camp, and burnt all that the blacks had on the ground. I there saw some of the policemen discharge their carbines, but there were no blacks in sight at the time. I saw one of the policemen shoot a dog which was lying in a "mi mi," or gunyah, but I don't know who it was; cannot say who fired the first shot, but I saw two fired, both at a dog ; I saw no shots fired at a tree. The police burnt the camp, but I saw no blankets destroyed; I saw waddies and spears lying about, but cannot say whether any of them were actually burnt. I never saw a deserted blacks' camp before; I believe there were four or five shots fired altogether. I did not see all that transpired, in consequence of having to attend the gentleman who met with the accident.

Constable Charles Dunning stated as follows:— I was one of the patrol who went out to the blacks' camp on Saturday week last; we started, five in number, from the barracks. The order given by Mr. Quirk to Sergeant Apjohn was to the effect that the blacks' camp should be destroyed, and the blacks driven into the bush. We were also directed to take our loaded carbines with us, which we did. When we got to the camp, near Breakfast Creek, orders were given for the blacks to remove, and they immediately dispersed; Sergeant Apjohn set fire to the first gunyah ; the blacks were then leaving; one remained behind, and Sergeant Apjohn sent me to take a spear from him; some went into the bush, and others went into a boat; there was hardly time given between the order to remove and the setting fire to the camp. I burnt one of the gunyahs myself, and I am certain that there was not sufficient time for the blacks to remove all their property. I saw a great deal of wearing apparel burnt, consisting chiefly of old clothes; I also saw two blankets burnt; Sergeant Apjohn gave the order; he was the first to set fire to the gunyahs; I saw no bread or tobacco burnt; the blacks property was not removed 15 yards from the fire ; I saved a fishing net which I returned to the blacks. The first shot was fired in about three minutes after our arrival at the camp on the bank of the river. The blacks were going along the road when the shots were fired; I don't know who fired the first shot, but I should say there were eight or nine shots fired altogether; the firing took place under the orders of Sergeant Apjohn, and I took part in it. Apjohn said he had just put a bullet through a tree, and ordered me to do the same, which order I obeyed, I loaded my carbine just before starting; the carbines were capped before we sighted the camp ; I did not discharge my carbine because it had been loaded sometime; it was only loaded the same afternoon. I went to the second camp a little behind the other police, and could not see all that took place. When we mounted the hill I heard brisk firing; I should say there were about twelve or fifteen shots fired at that place; I cannot say whether they were fired at the blacks, but they were filed in every direction; there were no blacks in sight at the time. I saw Constable Cox beat a dog belonging to the blacks, which he afterwards told me he shot. On returning to Brisbane we again discharged our firearms. I had nine rounds of ball cartridge, but I believe the other men who belonged to the Penal Police had 23; I had seven rounds remaining when I returned. I never heard any remarks made with regard to frightening the blacks. I never heard the order given at the barracks to remove the blacks, and "discharge those carbines," but it might have been given, as I was not within hearing at the time.

Chief Constable Quirk was here re-called, and testified to the number of ball cartridge with which the men had been supplied when starting for the blacks' camp, and the number they brought back.

[The case was then postponed until Tuesday.]

Constable Michael Burke deposed as under: I was one of the patrol party who went out on Saturday week last to the blacks' camp at Breakfast Creek; Sergeant Apjohn was in charge; we started at 3 o'clock in the afternoon ; the orders given by Upjohn were for the blacks to remove and take everything away with them ; I assisted in removing them; they seemed greatly alarmed, and left hurriedly; I called on several of them to come back and take away their clothing; their clothing was in the gunyahs, and I assisted to remove it ; I saw no blankets, waddies, spears, bread, or tobacco burnt. Sergeant Apjohn fired the first shot ; we had been three quarters of an hour before the last gunyahs was fired; the first shot was fired at a tree. Constable Cox fired the next, I think at an old mangy dog belonging to the blacks; I think I was the next to discharge, it was at the same tree as Apjohn fired at; I fired twice; there might have been more than ten shots fired altogether, we did not cap until the blacks disappeared, nor did we cap before we arrived at the camp. After burning the first camp we went to the second, but I saw no blankets, clothing, bread,or tobacco ; we saw some things belonging to the blacks which I preserved , there were no blacks in sight when I reached the second camp; there were two or three shots fired, one of which was from my carbine, I took out thirteen rounds of ball cartridge; I am certain I fired two shots altogether, but I cannot say whether it was two or three, nor can I give anything like a guess as to how many shots were fired by the men.

[Mr. Brown, addressing Mr. Quirk, said "I hope we shall not have many robberies or felonies, as some of you constables seem to be endowed with very bad memories."]

No threats were made to the blacks; we merely fired at a tree in order to discharge our pieces.

Mr. Brown; But you reloaded, and again discharged?

Witness: Yes your worship. Constable Dunning fired first, and I said I would fire at the same tree ; one of the police assisted to carry a sick blackfellow into the boat. On coming home we fired about four shots into a gum tree.

Mr. William George Higginson deposed as follows :—I was riding on the Eagle Farm Road on Saturday week last, when the police burnt the blacks' camp. When I arrived at the first camp I found it had been burnt; I did not see the whole of the affair as I had to attend one of our party who had met with an accident. When I first saw the camp I believe there were about 30 blacks present; I saw nothing belonging to them destroyed except their gunyahs; I heard seven or eight shots fired ; I went up to the top of the hill where I saw two distinct camps, one on the top and the second a little the other side; I saw no blacks, there were three or four shots fired there,—perhaps six; I fired one at a time; I saw no dogs shot, nor any bread or other property belonging to the blacks destroyed; neither did I hear any intimidating langauge used; I heard the police say to the blacks that they were to be off, as they (the police) had been sent out to burn their camps.

This concluded the investigation, whereupon Mr. Brown intimated that the Bench would draw up a report to the Colonial Secretary for the special consideration of the Government.

October 1860 - Reprimand for Chief Constable Quirk for 'greatly exceeding his duties' burning the Breakfast Creek camps

North Australian, Ipswich and General Advertiser (Ipswich, Qld. : 1856 - 1862), Friday 2 November 1860, page 3

LOCAL INTELLIGENCE.

THE LATE OUTRAGE ON THE BLACKS — At the close of the ordinary Police-court proceedings on Tuesday last, Mr. Brown summoned the attendance of Sergeant Apjohn and the other policemen concerned in the late burning of the blacks' camp near Breakfast Creek. Serjeant Apjohn and one or two others attended, and Mr. Brown at once read to them an extract from the minutes of the Executive Council, forwarded to him by the Colonial Secretary. It was to the following effect : — The Council having considered the report of the Police-Magistrate, with reference to the burning of the blacks' camps near Breakfast Creek, are of opinion that Chief-Constable Quirk greatly exceeded his duties, and that the measures adopted by the police were unnecessarily harsh and extremely censurable. They believe that the camp on the roadside was a nuisance, but they can not see in this, or any of the attendant circumstances, the slightest reason for the harsh and extraordinary measures adopted by the police. Such conduct was only calculated to provoke the hatred of the blacks, and thereby endanger the safety of the white people. The minute concluded by requesting the Police Magistrate to reprimand the constables concerned in the outrage; which his worship did, adding that the minute ought to be a warning to them in the future, and if it was not, a very different course would be pursued. — M . B Courier.

The inquiry into the burning of the Aboriginal Camps at Breakfast Creek and the subsequent reprimand to Chief Constable Quirk are an indication of:

- dispersal of camps was carried out by Town Police in the 1860's

- both Magistrate Brown, the Executive Council and presumably T.B. Stephens and the Mayor considered that Quirk was greatly exceeding the Chief Constables duty

- the reference to 'they believe that the 'camp on the roadside was a nuisance' could be referring to the Police Towns Act and the power to control nuisances

- the Moreton Bay Courier's headline 'Late Outrage On the Blacks' and the reprinting of it by another paper must indicate some degree of public opinion for a different approach to the 'unnecessarily harsh and extraordinary measures adopted by the police'.

1860s and 1870s - 'Reminiscence of Mrs J.J. Buchanan

1931 reminiscence in The Telegraph of 82 year old Mrs. J.J. Buchanan (born in Edward Street c.a. 1849) about the 1860s and 1870s included:

'The blacks were hunted out of the town by mounted police at sunset. Even so families going from Queen Street to the windmill on Wickham Terrace would make up parties because they were nervous of the Aborigines.' (http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article183335944)

Her reminiscence ends with:

'She also cherishes the greatest admiration for the fine old pioneers, who played their part in building up the "queen" city of the north," and of which she herself is one of the few survivors.'

This reminiscence provides evidence of:

- the curfew in the Wickham Terrace area of the town,

- that resistance to colonisation continued in the 1860s and 70s,

- an indication that the Town Police were not seen as adequate by white residents, and that

- colonialists put quite a bit of energy into reinforcing the meme of 'pioneering' as a wonderful thing.

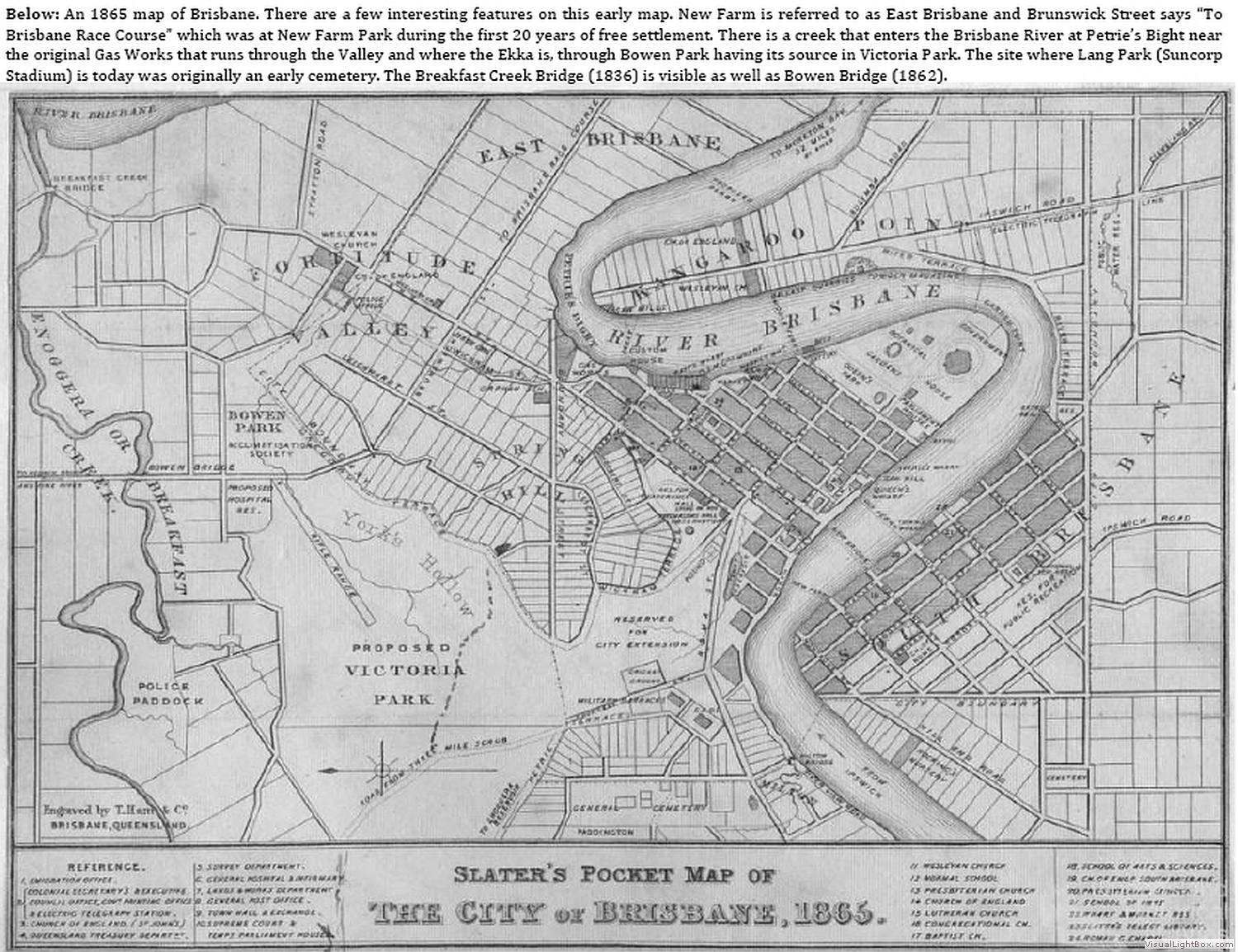

1865 'Slater's Pocket Map of the City of Brisbane, 1865'

• p. 17 'South Bank an historical perspective from then until now' (BCC Lib)

• this shows the extended 'city' boundary no longer using Boundary St. Spring Hill but crossing Whickham St around James St and following Gregory Terrace, skirting Yorks Hollow on the eastern side.

• shows Boundary St. West End marked as City Boundary, Musgrave Park marked as Res. for Public Recreation, and West End school site marked as Cemetery.

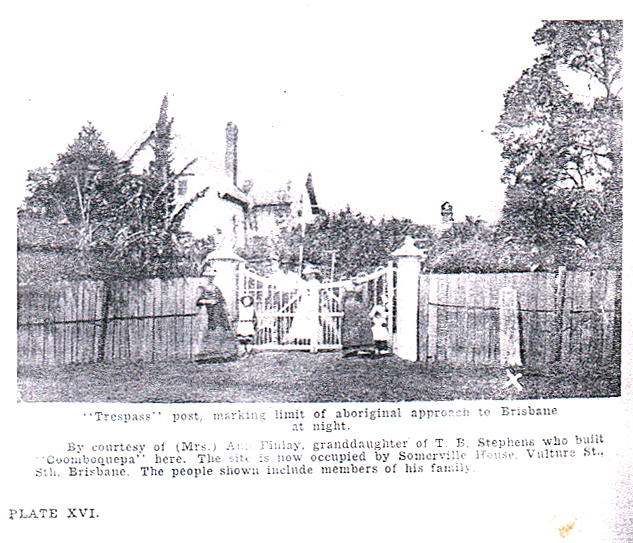

c.a. 1872 Photograph on Plate xvi of 'Triumph In The Tropics: an historical sketch of Queensland', compiled and edited by Sir Raphael Cilento with the assistance of Clem Lack; Brisbane: Smith & Paterson, 1959. Held Oxley Library, & FAIRA.

states:

"Trespass" post, marking limit of aboriginal approach to Brisbane at night.

By courtesy of (Mrs.)Ann Finlay, granddaughter of T.B.Stephens who built "Coomboquepa" here. The site is now occupied by Sommerville House, Vulture St., Sth. Brisbane. The people shown include members of his family.

The photo shows what appears to be a wooden post approx 1 m high, just outside their fence line. It has a sharpened top, presumably to help preserve it from the weather. In the print in the book there appears to be some writing or illustration of some sort on the post. In the copy of the image held by Qld State Library, this can not be seen however and it may be a reproduction artefact. The photo was taken by Boag around 1872 before the railway line excavation that caused the Stephens family to move and rebuild Cummbooqueepa on it's current site in the grounds of Sommerville House. It has been suggested that the photo is possibly taken from Stephens Road and not from Vulture Street. If this was the case, it would throw some doubt over whether it was actually a "Trespass" post as claimed in 'Triumph of the Tropics'. However, a close examination of the three images currently available in the Picture Queensland collection would seem to make it more likely to be taken from Vulture Street. This would make it more likely that the post was on Vulture Street thus adding validation to the 'Trespass Post' claim.

Note that the Police Towns Act required the provision of markers along the town boundaries and that fines for the removal or damaging of these markers was specified in the act.

Note that the reminiscence article (see below) by James Darragh about his memories of the 1870's and published in 1931 states that there was 'a large wooden post indicated one of the town boundaries' on the corner of Vulture and Wellington Roads. It would seem likely that town boundary posts did exist around that time at least on the corners but probably also on positions like outside T.B. Stephens house on Vulture Street.

Early 1870's - Mr James Cowlishaw - 'If you fire on them, I'll fire on you.'

F. E. Lord, ‘Brisbane’s Historic Homes,’ The Queenslander 12 May 1932 p 3 :

" Mr. Beal told me the other day, as a lad in the early '70's, he went with his father and the late Mr. James Cowlishaw on a fishing trip up Breakfast Creek. The blacks—men, women, and children—had all been driven down to the creek by the troopers at about sundown, as the custom was at that time, I understand, and as they were swimming across the creek, one of the troopers said to his mate: "Shall we fire on them?" Without waiting for the other man's reply, Mr. Cowlishaw shouted to the men: "If you fire on them I'll fire on you!"

http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article23148803

James Cowlishaw was born in Sydney in 1833. In 1873 he was elected to the Qld Legislative Council, was an architect, a mason, a director of the Brisbane Gas Company and or the Telegraph Newspaper Co.

This reminiscence is interesting in at least the following ways:

1) the curfew was being actively policed in the 1870s with Breakfast Creek likely to be a boundary

2) 'troopers' - are these Town Police or Native Troopers

3) 'troopers' were prepared to 'fire on Aboriginal families'

4) James Cowlishaw objected strongly

5) James Cowlishaw was armed (presumably)

6) a man with strong views about shooting at Aboriginal families was elected to the upper house of the Qld Government

7) the reference in the extended paragraph to the awareness of Meston that Mr Beal's 'father and family in general were always good friends to the blacks'

(Thank you to Bill Metcalf for suggesting this reference.)

1870's James Darragh - reminiscence - Town Boundary indicator on corner Vulture St and Wellington Road

The Brisbane Courier published a letter to the editor by James Darragh recalling memories of Kangaroo Point and surrounding area in the 1870's and published in the Brisbane Courier, Thursday 6 August 1931, page 19. He finished his letter with:

'On the corner of Vulture-street and Wellington-road a large wooden post indicated one of the town boundaries. There was a blacks' camp opposite Mowbray Park, The blacks paid daily visits to the Point, and I often saw Sergeant Collough turning them camp wards at dusk - I am, sir, &c., James Darragh.'

(The whole article is published in Dr. Ray Kerkhove's book 'Aboriginal Campsites of Greater Brisbane'.)

This is an interesting quote for a number of reasons. It points out where another of the town boundary posts existed in the 1870s. It also indicates a relationship between the town boundary and the curfew, that is, Darragh observed Sergeant Collough 'turning them camp wards at dusk'. Darragh remembers 'a blacks' camp opposite Mowbray Park'. This camp site would have been outside the town boundaries although close to the Wellington Road boundary.

late 1870's Carl Lentz's statement

Evans in 'Brisbane: The Aboriginal Presence' p.88 and Colliver & Woolston in 'Aboriginals in the Brisbane Area' p.64 quote Carl Lentz as saying

'even in the late 1870's mounted troopers would ride about Brisbane 'after 4pm, cracking stockwhips' as a signal for Aborigines to leave town.' (23)

1875 Newspaper letters debate about mounted troopers driving an Aboriginal group towards Breakfast Creek and

lobbying for 'establishment of reserves'

letter to the editor from Toowong in The Brisbane Courier Mon 3 May 1875

'Treatment of Aborigines.

TO THE EDITOR OF THE BRISBANE COURIER.

Sir, I was somewhat startled on reading the following extract from "Our Brisbane Letter," published in the Sydney Morning Herald of the 23rd April :-

We are suffering from the usual annual nuisance created by the distribution of blankets among the blacks. They are congregating in considerable numbers in camps near the city, and as, despite the law, publicans and others will supply them with drink by way of cheap wages for woodcutting and other odd jobs, the unfortunate creatures become noisy and offensive. They are not permitted to remain within the municipal boundaries after dark; but in order to enforce this regulation they are driven out at the point of the whip by mounted troopers. This process is anything but an elevating sight, reminding the onlooker more of the hunting of vermin than of the enforcement of law against human beings; and the way in which blackfellows, gins, and picaninnies will take to the water when too hard pressed by the horses, makes the vermin comparison still stronger.

It would appear from this that the aborigines of Queensland are hunted from the streets of Brisbane by mounted troopers armed with stock whips, to escape which they take to the water like rats to the great amusement, I presume, of our small boy population. When such fibs as these are vouched for by one of ourselves to the editor of the leading journal of the adjoining colony, it is no wonder that still more extravagant reports should be published and accepted as truths at the other end of the world. We have enough to answer for with respect to our treatment of the blacks, in all conscience, and rejoiced would I and many others be if, by the establishment of reserves or otherwise, they could be kept from the public house, and their position improved. But to say that the citizens of Brisbane stand calmly by and see half-clad women and children flogged through their streets by mounted troopers is too cross a libel for us to allow to pass without challenge.

Yours, &c,

May 1. 'TOOWONG.'

The letter writer with the pseudonym 'Toowong' is obviously concerned with the negative opinions of the Sydney papers and letter writers. He or she seems to also have a bad conscience about 'our treatment of blacks' and is lobbying for the establishment of 'reserves or otherwise where they could be kept from the public house, and their position improved.'

1875 letter to the editor The Brisbane Courier Sat 8 May 1875

The Police and the Aborigines.

To the editor of the Brisbane Courier

Sir- Having, been an eye-witness to what I consider a very curious proceeding on the part of the police I therefore request that you publish this for the information of the public. On Saturday, the 17th of April, I was standing on the verandah of this hospital, with some of my friends, when our attention was drawn to a crowd of people coming from Brisbane, some of them mounted. At a distance, it appeared to be what is called in the old country a drag-hunt; but as they approached to where we were standing we found that it was the police driving four or five (aboriginal) natives before them. They (the blacks) seemed to be fatigued from running, but that had no effect on those guardians of public order. As soon as the blacks commenced to walk, the police tried to ride over them with their horses, and when they came within reach of the natives, used their riding whips very freely on the backs of those unfortunate savages.

-Yours, &c, PATIENT.

General Hospital, May 1.

[We have cut down our correspondent's letter to the limits of the narrative it contains. The reflections are just, but not essential. - ED. B.C.]